Borders are strange places. Many are anti-climatic; often nothing more than two unimpressive huts in the middle of nowhere, straddling a strip of no-man’s land. Some are focal points of hostility and distrust; highly militarised, with guard towers and barbed wire creating an impenetrable barrier – for those without the correct documents, at least. Others are little more than a line on a map or perhaps a stream or river. Borders rarely seem to reflect natural or human reality; in many parts of the world, locals pay them little mind, crossing back and forth freely, as they go about their days.

Especially in Eastern Europe, where borders have moved time and time again, even in the last century alone, the patterns of language, tradition, cuisine and commerce sometimes bear little relation to these demarcation lines. Ideas about identity or nationality, too, often fail to fit neatly into internationally recognised borders. But on each side of the Polish-Ukrainian border, today, there’s one major distinction: between war and peace.

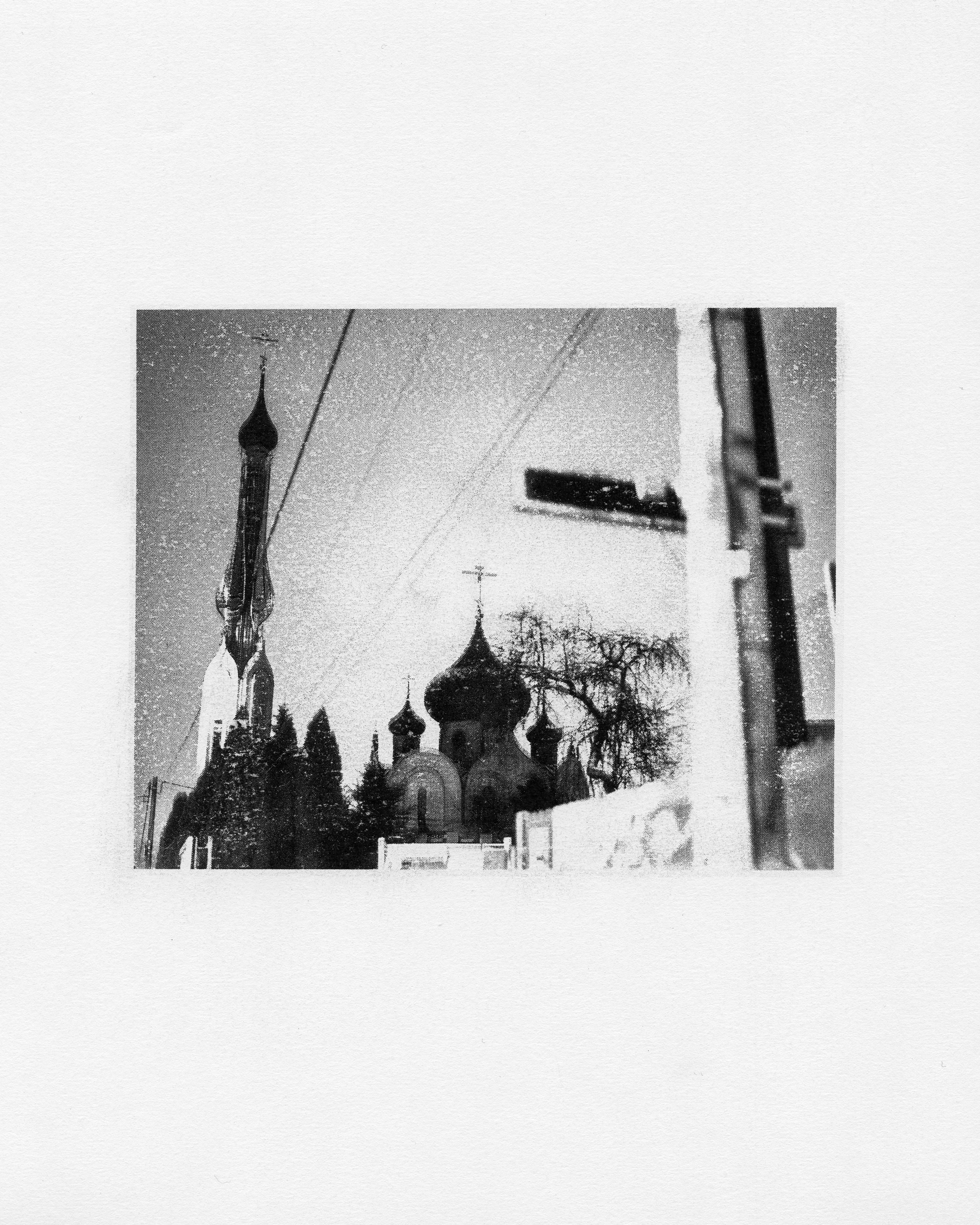

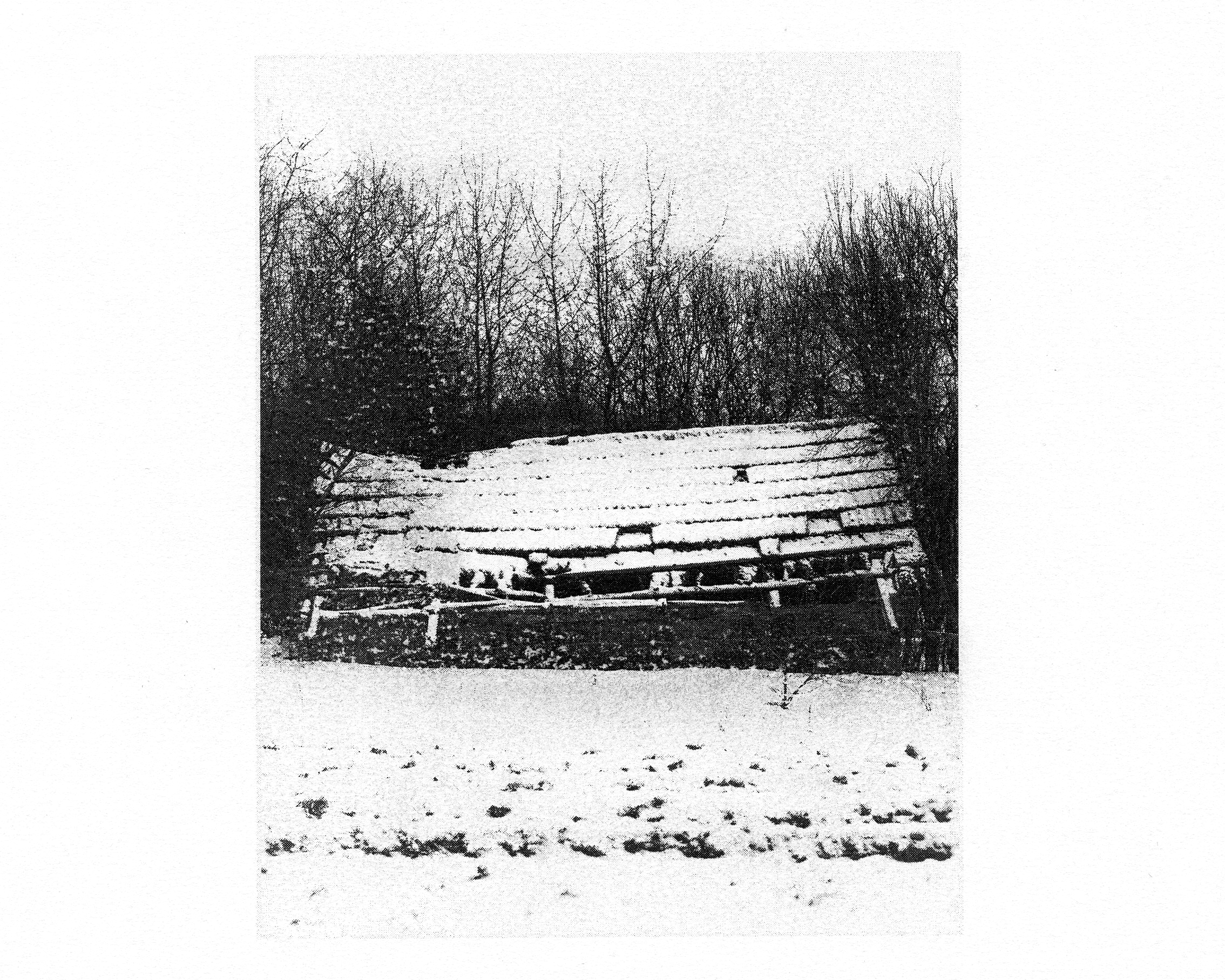

Yet, as Tommy Sussex’s The Borders of Poland series shows, even this division is much much less rigid and more porous than we might like to admit. While Tommy never crossed into wartime Ukraine during his journey along Poland’s border with Ukraine and Belarus in January 2023, the war is nowhere to be seen, yet present in every image. Fear lingers beneath every interaction, in every medium format photograph.

The post-Cold War optimism for dismantling borders and embracing the free movement of people is long gone. In recent years, Europe’s borders have become increasingly policed and militarised. Another so-called ‘migration crisis’ that began in 2021 on Belarus’ border with Latvia, Lithuania and Poland is a reminder of the violence of borders – and how they can be weaponised. As Europe’s fear of the other has grown, the barbed wire has blossomed on its southern and eastern frontiers. Fortress Europe is a reality, once again.

Yet, placing faith in borders as guarantees of security seems increasingly misplaced. Borders, treaties and international law meant little when Vladimir Putin ordered his infamous ‘special military operation’ and the world’s ‘second most powerful army’ launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Since then, every Russian military exercise and the Wagner PMC’s recent arrival in Belarus have raised concerns across the border in Poland.

In November 2022, a stray Ukrainian air defence missile struck a grain dryer in the Polish village of Przewodów, killing two Polish workers. While locals worry about a repeat of this incident, the real fear is that another mistake or miscalculation triggers a cycle of escalation that drags Poland directly into the war and the country becomes a battleground once again. For these are, after all, what historian Timothy Snyder has christened the ‘bloodlands’ – an area where untold blood and treasure has been expended since the dawn of history, as great powers from east and west have clashed here, wrestling for strategic dominance.

Far from the capital and centres of political power, those who live in north-east Poland feel little comfort in knowing that all that separates them from a hostile army is a metal border wall – or in some areas, just a river. For the approximately 1.4 million Ukrainian refugees who have arrived in Poland, crossing the border provides much-welcome relative safety. Many Polish people Tommy spoke to were proud of how their communities mobilised to welcome Ukrainians, offering food, water, shelter, Wi-Fi and other support. But for Poles, the Ukrainians’ presence is also a reminder of the proximity of the war next door. Here and across Europe, there’s a sense that the security situation is increasingly precarious.

After the outbreak of full-scale war, Tommy wrestled with how to continue documenting Ukraine’s story. It struck him how the rest of the world is observing this conflict intimately and in near real-time through news reports, social media and ordinary Ukrainians’ smartphone videos – but enjoying a level of abstraction not afforded to Ukrainians, who have to survive through it every day. So, he was drawn to Poland’s border with Belarus and Ukraine and to explore the feelings of people living closest to the conflict but with the degree of separation provided by the border.

Each of Tommy’s evocative photographs from the borderlands speak to a complex history, a tense present and an uncertain future. Like the very best photography, the series tells a story that speaks on many different levels, going beyond what’s visible in each image. Tommy’s connection and concern for Ukraine and its people is ever-present. We are made to feel the lingering threats. But perhaps most unsettlingly, the series captures the fragility and temporary nature of peace.

- Alex King (Huck Magazine)

Link to Huck Article

Link to Arena Magazine Article

Especially in Eastern Europe, where borders have moved time and time again, even in the last century alone, the patterns of language, tradition, cuisine and commerce sometimes bear little relation to these demarcation lines. Ideas about identity or nationality, too, often fail to fit neatly into internationally recognised borders. But on each side of the Polish-Ukrainian border, today, there’s one major distinction: between war and peace.

Yet, as Tommy Sussex’s The Borders of Poland series shows, even this division is much much less rigid and more porous than we might like to admit. While Tommy never crossed into wartime Ukraine during his journey along Poland’s border with Ukraine and Belarus in January 2023, the war is nowhere to be seen, yet present in every image. Fear lingers beneath every interaction, in every medium format photograph.

The post-Cold War optimism for dismantling borders and embracing the free movement of people is long gone. In recent years, Europe’s borders have become increasingly policed and militarised. Another so-called ‘migration crisis’ that began in 2021 on Belarus’ border with Latvia, Lithuania and Poland is a reminder of the violence of borders – and how they can be weaponised. As Europe’s fear of the other has grown, the barbed wire has blossomed on its southern and eastern frontiers. Fortress Europe is a reality, once again.

Yet, placing faith in borders as guarantees of security seems increasingly misplaced. Borders, treaties and international law meant little when Vladimir Putin ordered his infamous ‘special military operation’ and the world’s ‘second most powerful army’ launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Since then, every Russian military exercise and the Wagner PMC’s recent arrival in Belarus have raised concerns across the border in Poland.

In November 2022, a stray Ukrainian air defence missile struck a grain dryer in the Polish village of Przewodów, killing two Polish workers. While locals worry about a repeat of this incident, the real fear is that another mistake or miscalculation triggers a cycle of escalation that drags Poland directly into the war and the country becomes a battleground once again. For these are, after all, what historian Timothy Snyder has christened the ‘bloodlands’ – an area where untold blood and treasure has been expended since the dawn of history, as great powers from east and west have clashed here, wrestling for strategic dominance.

Far from the capital and centres of political power, those who live in north-east Poland feel little comfort in knowing that all that separates them from a hostile army is a metal border wall – or in some areas, just a river. For the approximately 1.4 million Ukrainian refugees who have arrived in Poland, crossing the border provides much-welcome relative safety. Many Polish people Tommy spoke to were proud of how their communities mobilised to welcome Ukrainians, offering food, water, shelter, Wi-Fi and other support. But for Poles, the Ukrainians’ presence is also a reminder of the proximity of the war next door. Here and across Europe, there’s a sense that the security situation is increasingly precarious.

After the outbreak of full-scale war, Tommy wrestled with how to continue documenting Ukraine’s story. It struck him how the rest of the world is observing this conflict intimately and in near real-time through news reports, social media and ordinary Ukrainians’ smartphone videos – but enjoying a level of abstraction not afforded to Ukrainians, who have to survive through it every day. So, he was drawn to Poland’s border with Belarus and Ukraine and to explore the feelings of people living closest to the conflict but with the degree of separation provided by the border.

Each of Tommy’s evocative photographs from the borderlands speak to a complex history, a tense present and an uncertain future. Like the very best photography, the series tells a story that speaks on many different levels, going beyond what’s visible in each image. Tommy’s connection and concern for Ukraine and its people is ever-present. We are made to feel the lingering threats. But perhaps most unsettlingly, the series captures the fragility and temporary nature of peace.

- Alex King (Huck Magazine)

Link to Huck Article

Link to Arena Magazine Article